The Equal Rights Amendment, a 21st-Century Issue

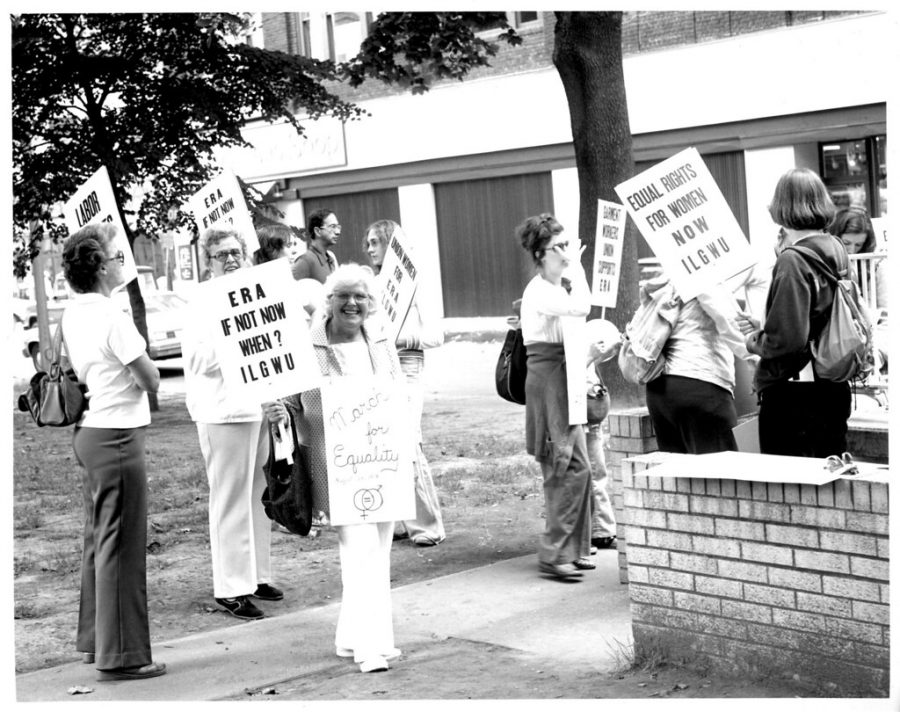

On November 7, 2020, Senator Kamala Harris of California became the first female Vice President-elect of the United States of America, and when she takes office on January 20, 2021, she will be the first female Vice President of the United States of America. This event is not isolated, the past couple of years have been rather empowering for women, a record six women ran for the 2020 Democratic presidential nominee ticket, in 2018, 117 women were elected to Congress, and in 2017, the MeToo movement drew and continues to draw much attention worldwide. This year also saw progress regarding gender equality with Virginia’s ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment on January 15th, 2020.

For those unaware, the ERA, or Equal Rights Amendment, is a constitutional amendment that was first proposed by women’s rights activist Alice Paul in 1923. It simply stated, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In 1972, the ERA was passed by Congress and began its path to ratification. For an amendment to become law, it must be passed by three-fourths of the states—38 states—unfortunately, the ERA was three states short by even the extended deadline in 1982. Since then, Nevada, Illinois, and now Virginia, have ignored the deadline and ratified the ERA anyway.

To still be entrenched in a fight for an indisputable right like equality between the sexes seems, or should seem, odd for the 21st century. Ms. Ann Gianfalla, AP United States History teacher, describes the amendment as an “of course” and those in government who do not support it as “sending such a misogynist message to citizens.” Mr. Walter Caskie, AP U.S. Government & Politics teacher, remarks the amendment is “a long time coming” and comments on its necessity saying “there’s a lot of issues with women where because they’re not the same sex as men they don’t get equal pay, they don’t get equal standing in certain job levels. So if they could be protected by their sex and have the justice system behind them I think that would be important.” Some argue the ERA is unnecessary as women are already protected from discrimination because of sex under the 14th Amendment. However, this interpretation is not widely established with conservative judges like the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia stating in an interview, “Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t. Nobody ever thought that that’s what it meant. Nobody ever voted for that.” The basis of Justice Scalia’s argument lies in the original intention of the 14th Amendment in the context in which it was enacted. The 14th Amendment, which established birthright citizenship, was ratified in 1868 during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era and was primarily meant to grant civil rights to the newly freed Black men. Section II of the amendment even specifically refers to only male citizens when talking about suffrage, hence the need for the 19th Amendment guaranteeing women’s suffrage in 1920. Ms. Gianfalla explains “some courts and some cases have interpreted the 14th Amendment to apply, but at any point the court could change their mind and get a conservative majority that would say the 14th Amendment doesn’t apply to women. So the ERA would ensure that could never happen.”

Not only would it enshrine an essential right into the Constitution, proponents of the ERA have hailed it as the solution to fixing the gender wage gap, strengthening legislation dealing with pregnancy discrimination, instituting higher standards for cases of domestic violence, and possibly providing a way to protect those who do not identify as either male or female. Despite the ERA’s simple wording, opponents have argued the ERA would lead to tax-payer-sponsored abortion and take away privilegs like gender-separate bathrooms, dorms, sports, as well as women-only scholarships. According to a Washington Post article written by Lisa Baldez, Dartmouth professor of Government, the ERA is unlikely to make such a dramatic effect like either side is predicting. Baldez writes it would likely indirectly affect Supreme Court decisions by “raising sex equality to the status of a fundamental right and increasing the standard that the Supreme Court would apply in determining whether a law that discriminates on the basis of sex violates the Constitution.”

Despite having 38 states ratifying the proposed amendment, the ERA has still yet to become a part of the supreme law of the land. When Congress passed the ERA in 1972, it was given until 1979 to garner the ratifications of 38 states. As the deadline approached, Congress worried not enough states would ratify the amendment and passed a bill extending the deadline to 1982. This attempt to amass more time to gather signatures failed, as the number of states who ratified the amendment remain stagnant at 35. However, with the ERA’s resurgence in recent years, many ERA proponents are hoping the deadline can be ignored to legitimize the ratifications of the states who passed the ERA long after 1982 and the amendment to be implemented as part of the Constitution.

Ultimately, Congress holds the power to change the deadline, although some legal experts have argued removing it retroactively may result in the case being brought to the Supreme Court. The House has already taken steps to abolish the deadline; in February 2020, it passed H.J. Res. 79, a joint resolution introduced by Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA-14) proposing the elimination of the ERA deadline. An identical bill has been proposed in the Senate (S.J. Res. 6), however Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has been quoted saying he was “personally not a supporter” by Reuters. Although it does not have authority over the deadline, the Office of Legal Counsel issued an opinion regarding it on June 6, 2020. They wrote that the United States Archivist who oversees the National Archives and Records Administration and certifies new amendments cannot certify the adoption of the ERA even if states like Nevada, Illinois, and Virginia ratify it past the deadline. They also affirm that the congressionally agreed upon deadline cannot be changed and the ERA is “dead” as not enough states ratified it before the deadline.

The push to pass the almost 100 year old amendment may be an uphill battle today, but ERA supporters have also been trying to start anew the entire amendment process by introducing a new ERA to Congress. In the House, Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-NY-12) has introduced H.J. Res. 35 which contains the original text following an additional “[w]omen shall have equal rights in the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction”, while Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) has introduced a related bill, S.J. Res. 15, in the Senate.